Harriet Berg was born in London in 1898: precisely why her parents were there at that time has not been ascertained, but as her father was a lawyer he may have been posted there by his firm.

It cannot have been a very long posting, for the Norwegian census of 1900[i] places him – Christian Hansson – and his wife Dagny at Bjerkheim in Bærum just outside Oslo. He is around 30 years of age, she 28 and they have probably not been married for a very long time, for their first child, Michael, is said to have been born in 1897. He trained as an engineer in Grenoble and later settled in the United States[ii]. The family had two servants: Emma Christine Moe, a 22-year-old from Tromsø (like Dagny), and Olufine Peders., who was the same age and also from northern Norway, but in her case from Malangen.

Ten years later, in 1910[iii], the family has moved closer to Christiania, to Huk Aveny 15, a fashionable district of villas and gardens, but close enough to the city that one could see the centre. Over the preceding ten years Harriet has been given two younger siblings: Ellen (born in Christiania 1902) and Per (born in Aker,1905). And the obligatory servants: three of them now. They were Gjertrud Olsen, 18, from Tønsberg; Oline Kristiansen, 25, from Tønsberg; and Ingeborg Halvorsen, 27 and from Horten.

Eldste barn var Michael Mørch Hansson, født 3. januar 1897, diplomingeniør fra Grenoble 1919, drog til USA 1919, død 1947. Gift Hjørdis Lund, født 1895. 1 barn. Kfr. slektstavlen. Nesteldste barn Harriet Mørch Hansson, født 8.4.1898, død 1975, gift Arild Kristofer Berg, født 28.7.1894 i Oslo. 3 barn. Kfr. slektstavlen. Per Mørch Hansson, født 6.7.1902, død 3.5.1903. Ellen Mørch Hansson, født 6.7.1902, død ved ulykkestilfelle i Paris 25.11.1919.

Harriet married the businessman Arild Berg from Høvik, just outside Oslo. This was announced[iv] by Kjeld Stub, the vicar at the garrison church in Christiania, Friday 8 August 1919. The marriage was celebrated[v] in her parents’ home on Bygdø, just outside Oslo town, 19 September the same year.

In a family history[vi] can be found a brief entry for Harriet:

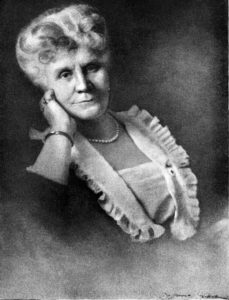

Harriet Mørch Berg,

born Hansson,

1898-1983

Thus, Harriet Mørch Hansson, married Berg, edited the weekly “We ourselves and our homes”. This was one of our most respected weeklies with high standards and elegant journalism. Harriet Berg held a long series of offices, especially in the Red Cross, and received honours in Norway, Sweden and Finland, apart from the King’s Medal of Merit in gold. In the book issued in connection with the 25th anniversary of her cohort of students she wrote “Admirer of unafraid personal effort””.

One of the first times Harriet Berg appeared publicly in a Red Cross context was in September 1945, when an appeal was launched by the Red Cross in Oslo, as in other districts, for people to become members – partly to support the ideals of the organization, partly to help finance the role of the Red Cross in meeting emerging needs now the occupation was over. Everywhere there is need the Red Cross is present – nationally and internationally, the ad in Friheten[vii] – a communist mouthpiece – said. And continued: “We appeal to all citizens of “the city with the big heart” and ask you to support us through membership and through contributions to our activities”. Annual membership cost NOK 2,40 – at the time around GBP 0.12.

In the spring of 1947, Harriet Berg’s magazine appears to have published an article which discusses the situation of women in America and Norway, comparing the two interviewing “experts” – psychologists etc – about the causes of increased stress and less polite children, standard fare for ladies’ magazines throughout the times.

This was picked up by a journalist who wrote under the name of Skule in Friheten[viii], the Communist Party mouthpiece. He refers to the magazine as one for society ladies and has a number ironic comments on the article – Anguished Women, parts of which were taken from Harper’s Bazaar – but doesn’t really engage Harriet: for his main concern is to use that article as his starting point for arguing something else: to make it illegal to hit children.

And: 40 years later, in 1987, that finally became the law in Norway.

Harriet Berg was elected, at some stage as member of the board of an NGO, Build your Country, which was founded just after liberation in 1945. But she didn’t stay very long, for at the organisation’s annual meeting in April 1947 she stepped down[ix].

One reason for stepping down from her role in Build your Country may have been a deeper involvement in the Red Cross in Oslo, where she was re-elected to the Board in June 1950[x].

Although Harriet Berg had stepped down as editor of the magazine, We Ourselves and Our Homes continued to use her as a writer, and in September 1951 an article about House for Handy Family with Children was published[xi].

Oslo Red Cross grew rapidly after the war, and continued to do so in the early 1950s: at its annual meeting[xii] – where Harriet Berg was re-elected to the board – it was announced that the membership had risen to 15’000 individuals, and that the activities had yielded a financial surplus of NOK 25’000, or GBP 1’253.

At the General Assembly of the Norwegian Red Cross in October 1954, Harriet Berg was elected Vice President of the organisation, replacing Mrs Ingrid Luet Cherat[xiii].

The Norwegian Red Cross, for decades, did not celebrate international Red Cross day but organised an annual “Red Cross Week” early in the autumn. In 1955, Norwegian Radio planned to transmit from the opening of this week, and a leading politician, Carl Joachim Hambro, and Harriet Berg both were speakers[xiv]. Carl Joachim Hambro was also the last President of the Assembly of the League of Nations and in that capacity handed over the archives and other possessions to the new United Nations.

In February 1956, wrote Arbeiderbladet[xv] – a newspaper then representing the Labour Party – Harriet Berg was one of the speakers at an occasion at the Red Cross’ “Sister Home”, where 27 new Red Cross Sisters received their diplomas. Other speakers included the Chairman of the Oslo Branch, Pastor Alex Johnson, ad Dr H. Ramstad.

In early 1956, We Ourselves and our Homes published its last issue[xvi], but at this point someone else was editing it – Harriet had returned to the magazine just after the war, but only for a short time.

In 1956 armed forces of the Soviet Union entered Hungary in order to restore that country to communist party rule. This caused a large number of Hungarians to flee to the West, first to Austria. The League of Red Cross Societies mounted a large-scale relief and assistance-operation, for which it received the Nansen Medal in 1957[xvii]. The form of the operation would, in modern terminology, perhaps be referred to as “co-ordinated bilateralism”, and drew on capacities and resources of member National Societies.

The Norwegian Red Cross, initially, sought to mobilize support for action within Norway, but soon came to the conclusion, in consultation with the Refugee Council (of which the Red Cross was a member) that resources might be better used elsewhere.

A piece[xviii] written for the 60th anniversary of the events concludes with the following paragraphs:

“I Norway the humanitarian organization the Refugee Council, later reorganized and given a new name in Norwegian, took care of Hungarian refugees.

Initially with assistance in the areas where the refugees had arrived, so that NOK 70’000 were telegraphed to the representative of the Refugee Council in Austria, according to the history book “Assistance and Protection. The Refugee Council 1946-1996”.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees appealed to Norway and other countries to receive refugees to be transferred from Austria, something the Refugee Council and Norwegian authorities initially rejected. In the first instance, one wanted to see whether many of the Hungarians might wish to return home.

And, presaging present day refugee debates:

“In any case all experience showed that the money reached farther when they could be used where the refugees were located – in this case, Austria”

Harriet Berg in the Red Cross advised that, according to plan, should have appeared in NRK’s The Housewife’s Hour and appeal to all housewives in the country to open their doors for Hungarian refugees. Following the decision of the Board of the Refugee Council these plans were suspended”

One of the duties, at least informally, of Vice Presidents of the Norwegian Red Cross is to participate in the annual meetings at the district level, Thus, in late May 1956, Harriet Berg was in Levanger for the meeting of Nord-Trøndelag District Branch. During the meeting she made a presentation of the international activities of the Norwegian Red Cross. On the Sunday there was a Red Cross mass in Alstadhaug Church, followed by a guided tour of that building[xix].

In September 1956 Harriet Berg travelled to Hetland by Stavanger, where the local Red Cross branch was celebrating Red Cross week in co-operation with Stavangerflint, a pottery. On the premises of that company, the Red Cross organised a “House-wives’ Market”, where they also served coffee and homebaked cakes and bread. On two of the days there would be a fashion show, and in the middle of the week Harriet Berg would give a presentation[xx].

In February 1957 Harriet Berg appeared on radio[xxi], in a programme called House and Home and made a presentation on the idea of “patient friend” – the term used by the Norwegian Red Cross for those volunteers who spend time visiting people who are hospitalised or otherwise isolated as a result of illness.

In April 1957 Harriet Berg was back at Bakkebø, where they opened the ninth “pavilion” on the property. The pavilion is described in the local newspaper[xxii] as the most beautiful of all of them and was opened by Bishop Smith.

The same year the Norwegian Red Cross held its National Meeting in Stavanger, and during that Harriet Berg was re-elected as member of the Board[xxiii].

The National Meeting also appointed the delegates of the Norwegian Red Cross to the International Conference which was scheduled to take place in New Delhi later in 1957. Harriet Berg was the leading governance person, and with her would travel the Secretary General, Sten Florelius, and Administrative Secretary Dagny Martens[xxiv].

This International Conference was mentioned in several newspapers (possibly “inspired” by the Norwegian Red Cross), including one in Grimstad[xxv], a small town on the south-east coast of Norway, and one with a traditionally international outlook resulting from the shipping business conducted from there, and the many sailors. The small article mentions the number of National Societies, that five more would be recognised during the Conference, and notes that “Red Cross Representatives from both East and West Germany, North and South Vietnam, and North and South Korea” would participate, in spite of the mutual rejection of their respective states. The article also refers to the 24th meeting of the League’s Board of Governors and at which there would be National Societies “from all 6 continents”. Among the issues to be debated, the newspaper mentions protection of civilians during wartime, especially in light of the continuing development of nuclear weapons.

At the next National Meeting, in the autumn of 1960, Harriet Berg was again elected to the Board of the Norwegian Red Cross[xxvi].

The Bakkebø home for intellectually disabled children became an independent foundation established by the Norwegian Red Cross through a Supervisory Board decision dated 23 November 1958. It had its own board, and Harriet Berg was a member of this, together with representatives of the Red Cross Districts concerned, and of the authorities in the same regions.

Mrs Heddy Astrup, who had chaired the project committee and since the opening of the institution’s board, had asked the Norwegian Red Cross to step down during the summer of 1961. At the following board meeting in June 1962, a new Chair was elected, and Harriet Berg became Vice Chair.

Bakkebø was, at this stage, a considerable operation: 300 children and 100 employees, but the Bard had ambitions and discussed expansion to a capacity of 400 children as well as a building for elderly[xxvii].

In the spring of 1964, Harriet Berg travelled south- eastwards – but only around 65 kilometres or an hour by train to Mysen where Østfold District of the Red Cross held its annual meeting. The District branch proudly announced it ha reached nearly 13’000 members and that the Red Cross Week had raised around NOK 400’000 – more than 20’000 pounds sterling. Harriet Berg made a presentation to the meeting: the topic was asthma, which she noted was a significant problem in Norway with more that 10’000 children awaiting treatment – and waiting times at the National Hospital very long. For that reason the Norwegian Red Cross had decided to build a home in the vicinity of Oslo. It would be an expensive project, and would represent a significant challenge for the organization in the coming years[xxviii].

In late 1964 preparations were well underway for the celebration, during the following year, of the 100th anniversary of the Norwegian Red Cross. Harriet Berg chaired the “Arrangements Committee” for the anniversary, which among other elements was to feature a membership drive with the motto of “Every Norwegian in the Red Cross”[xxix].

29 April 1965 there was a small ceremony at the headquarters of the Norwegian Red Cross[xxx]. The occasion was the award of the Norwegian Red Cross’ highest honour to Hans Høegh – who later served as Secretary General of the League – for his services to the Red Cross. Harriet Berg expressed the warmest thanks on behalf of Oslo District. Hans Høegh, subsequently, went on to become President of the Norwegian Red Cross and, then, Secretary General of the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

In 1965 the Norwegian Red Cross celebrated its 100th anniversary, and Harriet Berg was the chair of the committee organizing the events in that regard. One of those was a gala in the “Aula of the University of Oslo”, the city’s and, perhaps the country’s, premier premises for celebrations. The Association of Oslo Florists and that of Oslo Gardeners provided flowers for that, and also for the service in the Cathedral. Outside the brass band of the Norwegian armed forces performed in a nearby part from 11 am the same day. Reported[xxxi] the newspaper of the Communist Party.

In an earlier report, the Labour Party Newspaper, Arbeiderbladet, conveyed more of the programme. The meeting at the University Aula would be attended by the King of Norway; nearly all costs associated with the celebrations would be paid for by contributions from private sector or others; the Cabinet offered a dinner at the Castle of Akershus.

The first item on the programme was laying a wreath at the Monument to the Fallen at the Castle of Akershus, the same on the grave of Prime Minister Frederik Stang, the founder of the Norwegian Red Cross; at the bust of Fridtjof Nansen, and on the graves of eminent members of the organization. And there was devotional service in the Cathedral, presided over by Bishop Smemo, then the head of the Church if Norway. And – to cap it all – there were visitors from the Ethiopian Red Cross[xxxii].

The Board of Bakkebø met in late March 1966, at Bakkebø, So Harriet Berge – who still was the Vice Chair – probably travelled there by rail, a journey of 8-10 hours or so. The Board passed the accounts, which showed expenses of four and a half million NOK, or nearly a quarter million pounds sterling. Other issues before it, a new sports hall, roofing the swimming pool, improvements to the agricultural activities – it was quite a complex operation[xxxiii].

Oslo Red Cross had many activities in the late sixties and needed cash to keep going: in September 1967 the Red Cross held a 10-day bazaar in “The Craftsman”, a restaurant in central Oslo. Harriet Berg spoke at the opening, during which the Female Students’ Song Association sang[xxxiv].

After the war, the Norwegian Red Cross became involved in efforts to provide better care for children with intellectual disabilities, and responding to an idea put forward by three people – Kiss Tveit, Leiv Tveit and Heddy Astrup – a central institution for the southern three provinces of Norway was established in 1947. This institution – Bakkebø in Egersund – kept working until the early 1990’s when a changed attitude to children like this led to a reform away from institutions. Harriet Berg came onto the board of this at an early stage and was still part of it

In the summer of 1968, Bakkebø had been open for 20 year. From a first intake of 45 children, the institution had grown to 320, and the number of staff was now 140, and Harriet Berg was still Vice Chair of the institution[xxxv].

Harriet Berg edited a magazine – We Ourselves and our Homes” – from 1934 until it was closed by the occupation authorities in 1944, and during the war she joined the Red Cross. So it is reported in the newspaper Tromsø 27 August 1969[xxxvi], when they prepared their audience for a radio programme the same day at 2 PM, the “Midday Time”.

A Norwegian radio programme called, roughly, “the Midday Pause” aired daily at 2 PM – later at 1 PM – from 1966 to 1995 and was meant to engage the elderly. On 27 August 1969, Harriet Berg was scheduled to be interviewed, and the Arbeiderbladet[xxxvii] newspaper wrote about it the same day. She spoke about her career as an editor, and as a Red Cross person, and her social work during the war as in peacetime. Looking back at a life of cultural and social activity she ends with a quote from the ageing Arnulf Øverland: “… sorrows I have put away… tears are for children and the very young…”.

In the autumn of 1969, the Norwegian Red Cross organised its general assembly – the national meeting – in the town of Kongsberg, and among many other decisions honoured Harriet Berg and her many years of service. As reported in the Labour Party newspaper[xxxviii]:

«Harriet Berg

honorary member of

Red Cross

Kongsberg, Sunday (NTB)

At the Norwegian Red Cross’s 24th national meeting in Kongsberg on Saturday, Torstein Dale, Oslo, was re-elected as president of the National Association. Moy Nordahl, Fauske, was re-elected as Vice President, and as new Vice President after Jørgen Velle was elected Per Røiseland, Moss. Grethe Johnsen, Stavanger, and Lothar Larsen, Steinkjer were elected as new Central Board members. Kaare Michelsen, Bergen, and Oddborg Skattum, Gjøvik, became alternate members of the board. Hjørdis Kolbeinsen, Jørgen Jørgensen and Charles Østby stepped down from the central board.

Former chairman of the Oslo district, Harriet Berg, who has been active in the Norwegian Red Cross for 30 years, was named honorary member.

At the national meeting, the Norwegian Red Cross Medal of Merit was awarded to Leif Pihl, Sandnes, and Lillemor Haarseth Roheim, Jørstadmoen. The Norwegian Red Cross Relief Corps Medal was awarded to Oddbjørn Folleraas, Sogndal, Rolv Beyer, Sandnes, and Per Hornburg, Bodø. The Norwegian Red Cross plaque is awarded to Guttorm Friis, Kåre Krogstad, Kristian Søgnen and Asbjørn Vik.

The national meeting addressed the work program for the next three years, and the meeting advocated increased efforts by the Norwegian Red Cross at the international level, both in disaster relief and development assistance in the association area »

By 1970, when Harriet Berg was 72, a new generation and its views on social work was becoming the dominant voice in debates over how people in social distress ought to be supported. Apparently, Harriet Berg had written an article in the Red Cross Magazine Over alle grenser – “Across all frontiers” – on the roles of professionals and volunteers, respectively, in these fields. She seems to have used the language of her own generation, but setting her views in a modern context of rights rather than charity: the magazine article has not been available. Anyhow, this article provoked a reaction that was expressed in Arbeiderbladet[xxxix] in early August 1970 and in the form of a letter from a reader, Tone B. Jamholt.

Ms Jamholt pointed out a terminological error on the part of Harriet Berg, and went on to attack the use of the word “to help” in the context of social assistance, claiming it would demean the recipient. She went on to try and explain her views in a simplified form – seemingly oblivious of the intellectual snobbery implied by her own choice of words. Insisting on the primary role of the public sector, she grants that private organizations have the right to exist – but only as pressure groups or in order to shape attitudes – in the direction Ms Jamholt prefers.

Towards the end Ms Jamholt declares that she will not hide the fact that humanitarian organizations have done some good in the past, nor will she cast doubt on the good will of Harriet Berg, but believes that the humanitarians have constituted an excuse for the public sector not to act. And in conclusion, she accepts that people behave as good friends towards acquaintances, on condition it is not conceived of as help – humanity must exist without being organized. If that is not the case, then it will be necessary to study the structures and locate the errors.

What Harriet Berg’s reaction, if any, to this was is not known but the little episode has been included as an illustration of the hard-line debates that took place during the late 1960’s and through the 1970’s, and which led to quite radical changes in both the Red Cross and the wider world of Norwegian organizations.

Monday[xl], 14 June 1975, was a good day for Harriet Berg: she was received in audience by the King of Norway, Olav V. Several other people had the same honour that day: the Chief of Pensions, Olav Hagna; Dr. Sidney A. Rand, Northfield, USA; Mechanic Henry O. Brække; Foreman in a paper factory Trygve Bye, Carpenter Lars Jensen, Cellulose worker Håkon Johannesen; Foreman Arne Y. Johansen; and Wage-cashier Arthur Rød all from the town of Halden.

Harriet Berg died in Oslo just before the middle of April 1983[xli]. Her funeral took place in Vestre Krematorium at midday, Wednesday 20 April[xlii].

______________________________________________

[i] Folketelling 1900 for 0219 Bærum herred; https://www.digitalarkivet.no/census/person/pf01037029004460

[ii] Gunnar Christie Wasberg Fil.dr., Universitetsbilotekar emeritus, editor; “CHRISTIANIA-SLEKTEN HANSSON”, based on an earlier work of the same title by a S. H. Finne-Grønn, 1939; p 94; https://hansson.priv.no/slekt/slektsbok.pdf

[iii] Folketelling 1910 for 0218 Aker herred; https://www.digitalarkivet.no/census/person/pf01036372005867

[iv] Norsk Kunngjørelsestidende; Oslo, 08.08.1919; https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_norskkundgjoerelsestidende_null_null_19190808_37_291_1

[v] Morgenbladet; Oslo, 17.09.1919; https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_morgenbladet_null_null_19190917_101_470_1

[vi] Gunnar Christie Wasberg Fil.dr., Universitetsbilotekar emeritus, editor; “CHRISTIANIA-SLEKTEN HANSSON”, based on an earlier work of the same title by a S. H. Finne-Grønn, 1939; p 94; https://hansson.priv.no/slekt/slektsbok.pdf

[vii] Friheten (Oslo); Oslo, 22.09.1945; https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_friheten_null_null_19450922_5_121_1

[viii] Friheten (Oslo),

Norge, Oslo, Oslo, 09.04.1947

https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_friheten_null_null_19470409_7_81_1

[ix] Halden Arbeiderblad, 02.04.1948, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_haldenarbeiderblad_null_null_19480402_16_75_1

[x] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 17.06.1950, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19500617_62_137_1

[xi] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 08.09.1951, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19510908_63_208_1

[xii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 05.06.1953, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19530605_65_127_1

[xiii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 14.10.1954, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19541014_1954_238_1

[xiv] Radioprogrammene for uken, Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 25.08.1955, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19550825_67_196_1

[xv] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 09.02.1956, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19560209_68_34_1

[xvi] Nordisk Tidende, USA, 22.03.1956, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_nordisktidende_null_null_19560322_66_12_1

[xvii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nansen_Refugee_Award

[xviii] https://www.abcnyheter.no/nyheter/norge/2016/10/20/195250240/sondag-er-det-60-ar-siden-oppror-brot-ut-i-ungarn-mot-sovjet-diktaturet

[xix] Innherreds Folkeblad Verdalingen, 25.05.1956, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_innherredsfolkebladv_null_null_19560525_51_39_1

[xx] Rogalands Avis, 03.09.1956, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_rogalandsavis_null_null_19560903_58_204_1

[xxi] Rogalands Avis, Stavanger, 08.02.1957, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_rogalandsavis_null_null_19570208_59_33_1

[xxii] Dalane Tidende, Eigersund, 26.04.1957, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_dalanetidende_null_null_19570426_73_47_1

[xxiii] Rogalands Avis, Stavanger, 30.09.1957, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_rogalandsavis_null_null_19570930_59_226_1

[xxiv] Friheten (Oslo), 03.10.1957, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_friheten_null_null_19571003_17_228_1

[xxv] Grimstad Adressetidende, 31.10.1957, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_grimstadadressetiden_null_null_19571031_102_125_1

[xxvi] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 10.10.1960, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19601010_72_236_1

[xxvii] Dalane Tidende, Norge, Rogaland, Eigersund, 02.07.1962,https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_dalanetidende_null_null_19620702_78_75_1

[xxviii] Moss Dagblad, 22.04.1963, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_mossdagblad_null_null_19630422_52_91_1

[xxix] Moss Dagblad, Norge, Viken, Moss, 28.12.1964,https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_mossdagblad_null_null_19641228_53_300_1

[xxx] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 30.04.1965, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19650430_1_99_1

[xxxi] Friheten (Oslo), 18.09.1965, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_friheten_null_null_19650918_26_213_1

[xxxii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 18.09.1965,https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19650918_0_216_1

[xxxiii] Dalane Tidende, Norge, Rogaland, Eigersund, 01.04.1966, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_dalanetidende_null_null_19660401_82_38_1

[xxxiv] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 06.09.1967, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19670906_0_206_1

[xxxv] Dalane Tidende, Norge, Rogaland, Eigersund, 15.07.1968, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_dalanetidende_null_null_19680715_85_79_1

[xxxvi] Tromsø, 27.08.1969, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_tromso_null_null_19690827_72_196_1

[xxxvii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 27.08.1969,

https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:nonb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19690827_1_197_1

[xxxviii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 06.10.1969, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19691006_null_231_1

[xxxix] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 04.08.1970, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19700804_1_178_1

[xl] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 17.06.1975, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladetoslo_null_null_19750617_0_135_1

[xli] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo); 15.04.1983; https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladet_null_null_19830415_100_85_1

[xlii] Arbeiderbladet (Oslo), 19.04.1983, https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digavis_arbeiderbladet_null_null_19830419_100_88_1